|

|

|

|

|

|

|

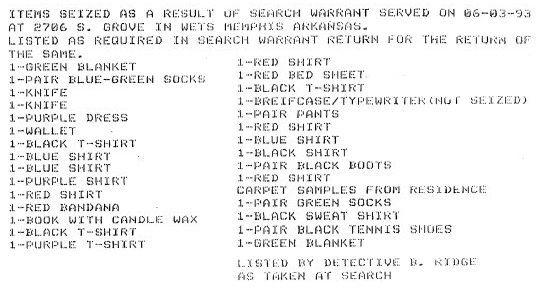

Items seized during raid of Echols trailer. (Original list made into two columns.)

Misskelley's Many Confessions, Part Two

After Jessie's June 3rd confessions Damien Echols and Jason Baldwin were arrested in a midnight raid. The state of Arkansas requires "police to conduct searches between 6 a.m. and 8 p.m. unless the circumstances in which the objects are to be seized are 'difficult to predict with accuracy' or when there is imminent danger that evidence will be removed." [law as cited in Commercial Appeal, June 29, 1993] In order to obtain the warrant, the police had argued that the cult would move to destroy evidence.

Which other individuals of the community and witnesses had verified their participation in the cult was not stated.

Perhaps the police expected a quick resolution to the case, that they would find damning evidence. What they confiscated was a lot of clothes. Perhaps they expected one defendant turning on the other or accepting a plea bargain. What they got was three defendants pleading innocence. Perhaps they expected a mental illness plea. Just five years earlier, Barbara McCoy who lived down the street from the Moores and Byers had pled insanity for the murder of her two children during an exorcism. She received a 13 month stay at a mental hospital.

Misskelley's court-appointed attorney Daniel Stidham expressed reluctance to take the case - he had an eight year old child of his own. Nevertheless, he hoped, since Misskelley had confessed, it would be a simple matter of arranging a plea bargain in exchange for Misskelley's testimony. He went on to describe his first encounter with Misskelley. "Here he was, a pitiful dwarf of a kid, sitting on a picnic table in the center of his cell wearing an orange jumpsuit that was too big for him. He didn't look up or say anything. He just stared at the floor." [Arkansas Times, James Morgan, 1996]

With this first encounter, Misskelley confessed to his lawyer. Stidham noted that although Misskelley maintained he was present at the murders, he could not give a narrative of what happened and some of his information was inaccurate.

Even while confessing to Stidham, Misskelley maintained his innocence to his father. "In a letter from the Cross County Jail in Wynne, Ark., received by the family Monday afternoon, Misskelley denied involvement in the slayings. 'I hope that y'all don't hate me because I did not do it,' Misskelley wrote, saying he spent the day on a roofing job with a man named Ricky Deese. 'I can not stand (it) in here much longer. I will go crazy,' the letter said at one point. 'Please try to get me out. I will die in here.'" [Commercial Appeal, June 9, 1993]

Among the items seized from Misskelley's trailer was a shirt with a bloodstain on it. Misskelley claimed he had cut himself on a bottle. The police found that this blood matched that of the victim, Michael Moore, the odds of such a match calculated at 7.2%. However, Misskelley was found to have the same blood type. Stidham began to consider the possibility that his client was innocent. Stidham had Misskelley's polygraph re-examined. Dr. Warren Holmes, at the time one of the foremost experts in polygraphs, volunteered to look them over. He concluded that the polygraph did not show Misskelley lying when he said he was not a member of a cult or was not involved in the killings. Stidham concluded that he had a lawyer's worst nightmare - an innocent client prone to confessing.

Misskelley's trial began January 26th, 1994. Misskelley's defense argued that he had been coerced into confessing and that his confession did not match the facts of the case on key issues. The prosecution presented evidence that Misskelley's confession was voluntary and that he had declared in his statement that he was not afraid of the police - showing he was not intimidated. Furthermore, they argued the confession did match the facts on other issues.

Misskelley's lawyers put up seven witnesses who said he with a group at the trailer park between six and seven in the evening when the police came to investigate an unrelated incident at a neighbor's place: James McNease, Charles Ashley, Jr., Jessie Misskelley, Sr., Christy Jones Moss, Susie Brewer and Louis Hoggard. Two police officers who were present at the scene testified that they did not see Misskelley there and one more testified he did not recall. It was surprising that the two officers could recall who was not among those at the scene of a minor incident report: they were interviewed about the event six months later, November and December of 1993.

Another four witnesses testified that Misskelley went wrestling with them that evening: Freddie Revelle, Dennis Carter, Jr., Roger Jones and Keith Johnson, leaving about 8 p.m. The prosecution sowed doubt that they were remembering the correct dates. The trial finished on February 3, 1994.

In later appeals, Dan Stidham alleged there was improper interference during the jury deliberations.

On February 4, 1994, Misskelley was convicted of three counts of murder and was sentenced to life in prison for the murder of Michael Moore and 20 years each for Branch and Byers.

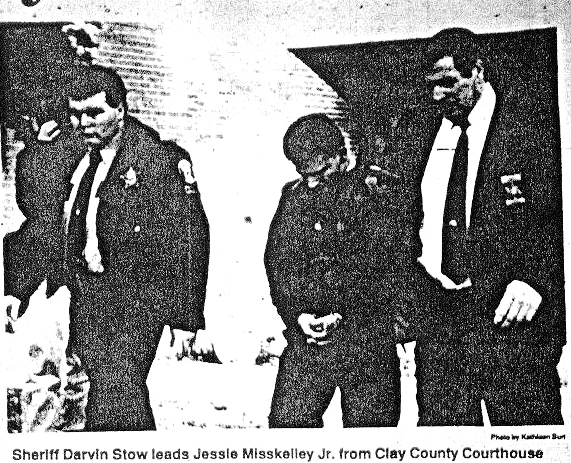

Misskelley reacted to the verdict with panic. "Just before sheriff's deputies took him to prison to begin a life sentence in the murders of three young boys, 18-year-old Jessie Lloyd Misskelley Jr. wept. ''He said, 'I'll never make it down there. I'll never get out and come home,' '' said his father, Jessie Lloyd Misskelley Sr., of Marion. ''I told him, 'You're stronger than that; you're stronger than me.''' [February 6, 1994 Commercial Appeal]

The Police Car Confession.

The prosecution had their own sort of panic. The constitution guarantees the right of defendants to face their accusers. Without Jessie attesting to his confession, it could not be used in the trials of Baldwin and Echols. The prosecution discussed with the victims' family the outlook. "All is not lost if he doesn't testify. But the odds are reduced significantly." [Prosecutor John Fogleman, Paradise Lost documentary] Davis approximated those odds: "Fifty-fifty might be good." [Prosecutor Brent Davis, ibid]

On February 4th, Misskelley confessed to the deputies transporting him to prison. "Deputy James Lindsey and myself [Officer Jon Moody] were transporting Jessie Miskelley to the Arkansas Department of Corrections at Pine Bluff. Jessie was asked if there was anything he wanted to say and after being assured we could not use anything he said against him in court, he chose to talk." [Officer Moody incident report, February 5th, 1994] By this time Misskelley had listened to an entire trial full of evidence. His confession appears to be a confused mash-up of presentations by the prosecution and defense.

Jessie pulled information from the defense. The defense asserted that in his June 3rd confession, Jessie had said the victims were held by a headlock but then had been led by Inspector Gitchell over the course of several questions to say that the victims were held by the ears. Ultimately, Jessie said, "By their ears and pulling them and stuff." [June 3rd, second taped confession] Even though on tape, Jessie denied he said this during his confession to the transport officers, "Jessie said he did not mention the 'ears' to the police, only a headlock." [Officer Moody incident report, February 5th, 1994]

Another statement seems to be referring to the police officers who testified they did not see Jessie at the trailer court at the time of their incident report. "Jessie stated that Officer Callahan had lied in Court about not seeing him on May 5th." [ibid - although the officers were Dollahite, McCafferty and Oliver]

The defense made a major point that Jessie misidentified the time of the crime and that he said the victims were tied up with rope when in reality they were tied with shoestrings. In deference to the prosecution, Jessie stated why he made these errors. "Jessie said he lied about the time and the rope to 'trick the police and to see if they were lying.'" [ibid]

Jessie added new details. "Jessie said they were hiding behind bushes when Damion grabbed Michael Moore." [ibid] "Jason had a 'bucktype locking knife' and 'cut it all off [from context, Byers' penis] and threw it in the weeds.'" [ibid] In contrast, the police stated testified they did a grid by grid search of the area.

Beyond this, the notes mostly reiterated Jessie's previous confessions including the rape of the victims, the phone call before and after the crimes and Jessie leaving before the crimes were finished.

Perhaps most critical was this note. "Jessie claims he has felt sorry for what has happened and talks as if he wants to testify against the other boys so they will not go free and to help himself." [ibid]

The Post-Trial Taped Confession.

Misskelley's police car confessions led to one of the most audacious incidents in the case. The prosecution tried to arrange a deal with Jessie, to reduce his sentence in exchange for his testimony in the upcoming trials. First, they met with Jessie's lawyers. They remained unconvinced. While it might be in Jessie's best interest to testify in terms of a reduced sentence, Stidham believed in his client's innocence. He could not suborn perjury. The prosecution pleaded with Jessie's father to convince him with the same lack of success.

A head-on assault not working, the prosecution proceeded to talk to Jessie without his lawyers' consent. After some preliminary interviews, the police transported Jessie from his prison to a jail in Corning to be nearer to the upcoming trials. There, another taped interview was planned. Dan Stidham later stated he learned about the transfer on the evening news. Together with his law partner Greg Crow, they rushed to Corning to intervene on behalf of their client. They insisted their client not make a statement. Stidham called Judge Burnett at home to stop the proceedings or to delay it until Misskelley had a psychiatric exam that had been requested earlier in the week. Burnett described receiving the call. "Y'all were asking me to make a ruling from my den where I was watching TV in my underwear." [Judge Burnett, February 22, 1994 Hearing]

On Thursday evening, February 17, 1994 Jessie's next taped confession began with admonitions from his lawyers.

The confession took place at the office of Joseph Calvin, deputy prosecuting attorney for Clay County. Prosecutor Brent Davis undertook most of the questioning with Calvin adding several questions.

Excluding procedural matters, Jessie made 193 responses to questions*. Again, the interrogators spoke the majority of the words, 2593 to 1449 words from Jessie. Ninety questions were yes/no, 53 requests for details and 32 were open ended. The open ended questions often took the format "What happened next?" [*These statistics are based on the official transcription presented here. There are errors in this transcription. Questions that were repeated were sometimes left out.]

Unlike the June 3rd taped confessions, Jessie often responded he did not remember (16 instances). This may have been due to the increased time that had passed or because Davis specifically phrased questions asking whether he remembered.

Misskelley couldn't even remember whether he could remember.

Misskelley described the face cut as a scratch.

Misskelley now said that the victims weren't raped. Several exchanges, although the following summarizes them.

Misskelley incorporated all of his alibi into the events.

At the end of this confession, Jessie's lawyers added their opinions to the tape.

Over the next several days, the prosecution continued to meet with Misskelley at his prison cell. According to Davis no tapes or notes were made. [February 22, 1994 hearing].

The Fiery Aftermath

Stidham was furious. In a hearing on February 22nd, Stidham raged that there had been prosecutorial misconduct and insisted the court initiate an investigation.

Stidham claimed that his client had been kidnapped and that the prosecution had dangled permission to have his girlfriend visit him in prison as a reward for cooperation.

Davis countered that he had been in contact with co-counsel Greg Crow and the transfer and interview was done with Crow's consent. Davis stated that Stidham had lost his perspective and was not pursuing the best interests of his client.

Davis further stated that Crow had insinuated that Stidham had not only lost his perspective, but was losing his mind.

Stidham disputed Davis' account, saying that Crow had not given consent for such a meeting.

Crow was not at the hearing, he had a conflict due to an unrelated deposition. Stidham offered Crow's affidavit - an important account that I don't have available. Judge Burnett, however, did read a portion into the record.

Judge Burnett rejected Stidham's arguments. He fired Stidham - partly.

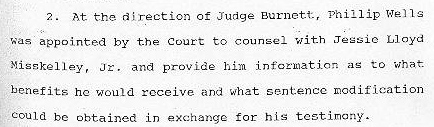

For matters related to negotiating Misskelley's testimony, Burnett appointed another attorney, Phillip Wells.

With the prospect of Misskelley testifying the other defendants' attorneys joined in the melee and matters became topsy-turvy. Echols attorney Scott Davidson, brought up the matter of a tape that Stidham had said he had played to the prosecution announcing that Misskelley would not testify.

Ultimately, Misskelley declined to testify.

The Statement in the Appeals

Referring to Misskelley's February 17th statements, Burnett declared,

By Arkansas law, the initial appeals are reviewed by the trial judge. As part of the proceedings, Burnett did take into account Misskelley's February 17th statements, a decision upheld by The Supreme Court of Arkansas.

The statement was attached in response to Echols request for DNA testing. Oddly, even though the issue was DNA, it was the only attachment.

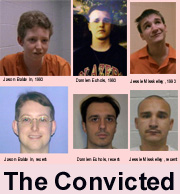

Misskelley at the time of arrest.

|

Copyright © 2011 Martin David Hill

|