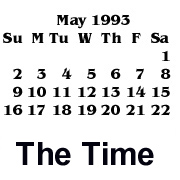

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

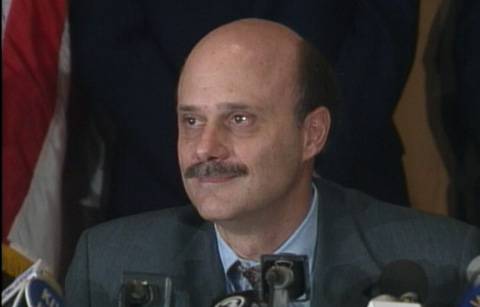

Gitchell at press conference announcing the case an "11." Reporter:

On a scale of one to ten, how solid do you feel your case is?

Chief Investigator Gary Gitchell: Eleven. [Press conference, June 4, 1993] Although Gitchell declared the case an eleven, in reality, the evidence against the three was slim. The supporting documents for the warrants were: a statement from William Jones saying he had heard Echols admit to the murders (but not implicating Misskelley or Baldwin); the missing children's report and the case summary implicating no one; Misskelley's confession, and Exhibit B, detailing why Misskelley's confession was accurate. Soon William Jones would retract his statement, claiming he only told the police what they wanted to hear. Misskelley would recant his confession and without his testimony to back the confession, it could not be used at trial against Baldwin or Echols. No evidence that would eventually be used at trial had yet been developed against Baldwin. The only trial evidence at this point developed against Echols was that provided by the Hollingsworths, who would place him a couple of hundred yards from the crime scene that night, and his police interview. Detective Bryn Ridge, present for the Misskelley confession, had great faith in it, vouching for it to the judge when seeking the search warrants. Later he defended it to the mother of Jason Baldwin, Angela Grinnell. Ridge:

Well it's like this. We've got a story that is very, very

believable. It is so close to perfect that we have to believe

it. [Interview with Terry

and Angela Grinnell, June 4, 1993]

Common practice would be to have the supporting documents for the warrants made available to the public. The day after the arrests the court sealed the documents, not allowing the public to learn about the paucity of the case. The West Memphis Evening Times ran an editorial bemoaning this decision. Mystery

will continue to surround the case of the three young West Memphians

found murdered last month, and the three teens accused of killing them,

in the wake of a judge's decision to close the basic documents on which

the youths' arrests were based. Circuit

/ Chancery Judge Ralph Wilson agreed with prosecutors that sealing the

arrest and search warrants would violate the rights of Michael Wayne

Echols, Charles Jason Baldwin and Jessie Lloyd Misskelley Jr. to due

process - that is, to a fair trial untainted by prejudicial pretrial

publicity. But

we wonder if the judge's ruling isn't apt to cause exactly the opposite

effect. [West

Memphis Evening Times, June 8, 1993]

The editorial concluded, But

the case remains shrouded in secrecy, and the public's questions remain

unanswered. We hope, above all else, that our faith in the

law

enforcement and judicial system is justified. We just wish we

knew for sure. [ibid]

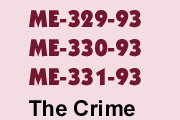

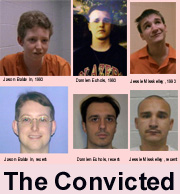

The Case for Innocence - Jessie Misskelley, Jr. On June 3rd, 1993, then seventeen-year-old Jessie Misskelley, Jr., confessed to participation in the murders of three children, Steve Branch, Michael Moore and Christopher Byers. He named eighteen-year-old Damien Echols and sixteen-year-old Jason Baldwin as the killers. There would be no "West Memphis Three" if not for the confession of Misskelley. As was pointed out by the Arkansas Supreme Court, no other evidence was presented as to Misskelley's guilt - no physical evidence nor eyewitness evidence to place him at the scene, nothing but his word. His innocence should be considered as an independent matter. None of the evidence against Echols or Baldwin reflected on him, other than, if they were guilty, Misskelley was correct in pointing their way. As pointed out by his attorney, Jessie Misskelley lied. He either lied during the several iterations of his confession or else he has been lying when he has claimed innocence. It is easy to understand the motivation of someone who would lie to claim innocence. It is difficult to comprehend why someone would falsely confess. Such behavior runs against common sense and self-preservation. We cannot imagine doing such a thing ourselves. His defense had this uphill battle to explain why he had confessed, arguing he was coerced by the police or else his low IQ made him susceptible. The coercion was suggested to be of the subtle variety, the police enticing him to seek approval, to join in the circle of the righteous, or to receive the money reward. It was also suggested to be of the blatant variety - threats and intimidation. Divining the reason for Misskelley's confessions involves supposition and inference. It is impossible to determine his true motives and it is also unnecessary. For whatever reasons, instances of false confessions exist. The primary question is: is this one of them? The police and the prosecution put forward that this was not just an admission of guilt, but that he had supplied information only someone present at the murders would know. As quoted above Detective Ridge claimed Misskelley's statements were "close to perfect." Below is an analysis of the state's closing arguments in the Misskelley trial, focusing particularly on the issue of guilty knowledge. The Case Against Misskelley - the Prosecution's Closing Arguments The prosecution made two sets of closing arguments, bookending those of defense attorney, Daniel Stidham. These arguments echoed one another. The prosecution's main points were: #1) Misskelley's confessions were not coerced; #2) Misskelley's confessions contained details he could only have obtained from being present at the murders; #3) The mistakes in Misskelley's confession were few and minor; and, #4) Misskelley's alibi was faulty. Other parts of his closing were directed away from Misskelley, at the evidence against Echols and Baldwin, ridiculing the theory that Mr. Bojangles was involved and describing the reasons for a lack of evidence. Because the confession is the evidence that convicted Misskelley, I will focus on this. The Matter of Coercion The defense tried desperately to explain why Misskelley confessed. They presented two expert witnesses to discuss the nature of coercion and its telltale signs. Warren Holmes was an expert in interrogation who had worked on over 1200 murder cases, including the assassinations of John F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King, Jr. Dr. Richard Ofshe was a professor of sociology at Berkeley with his PhD from Stanford. He had researched the psychological and sociological methods of persuasion for thirty years, had published five books and numerous articles, and had won the Pulitzer Prize for assisting in the investigation of mind-control tactics of Synanon. In the recent past, he had specialized in false confessions. In his closing arguments, Fogleman spent a considerable time ridiculing these experts and their credentials. Presented below is only a fraction. Then

we get to Mr. Ofshe or Dr. Ofshe, as, whichever one you

prefer.

But Dr. Ofshe or Mr. Ofshe, he can't treat a broken arm, he can't treat

your mind, he's not a licensed psychologist, you can't be licensed as a

social psychologist. He is a professor and a professional

witness. I will say this. Just because you hold

yourself

out as an expert in something doesn't make you an expert.

Just

because you come in with a lot of degrees and a Pulitzer

Prize.

But as you heard Dr. Reichert, it may as well have been the Heismann

Trophy. The Pulitzer Prize has no relevance to scientific

testimony. None. He's from Berkeley, California and

he came

and put on a show.

[Fogleman closing arguments, Misskelley trial]

Fogleman went through the confession, pointing out examples of how questions weren't coercive or merely directed at getting Misskelley to agree with the police version of events. What

occurred while you were there? (Quote from Det. Ridge) Any

manipulation, suggestion or leading in that question? [ibid, beginning

with a

quote from Misskelley's confession]

The question noted above is an example of good interrogation technique: an open-ended question. Out of the 340 questions presented to Misskelley during the recorded confessions, twelve were open ended. Fogleman pointed out there were other questions that were leading, but Misskelley chose to reject the police's offering. Have

they got their clothes on when you saw them tied? That's a

leading question, suggesting that they had their clothes on. He

says, no, they had them off. [ibid]

The police asked Misskelley 211 yes or no questions, in fact, the interrogation can be characterized by the police presenting Misskelley information and case facts and Misskelley agreeing or disagreeing. Misskelley answered no to thirty-eight. Often it was for minor technical reasons, such as the police repeating a question in a way that no corresponded to what Misskelley already said. There were several instances when Misskelley said no to substantive questions, such as the one Fogleman cited above. Although this is potentially substantive, in another exchange Misskelley said he wasn't there when the victims were tied (cited below). In many, many other exchanges he merely agreed with the police, even when the police offered obviously incorrect information. Insider's Knowledge And

I don't care what he [Stidham] says -- he can say there's newspaper

articles or what else, but you can read in that statement that when he

describes the castration of that particular boy, that is a fact that

only someone who was there could know. And when he describes that the

other two individuals forced them to perform oral sex on them, and

grabbed them by the ears, those are facts that only a person there

would know. When he describes the cutting on the side of one boy's

face, those are facts that only a person that was there would know.

[Prosecutor Brent

Davis, closing argument, Misskelley trial]

Fogleman and Davis cited the following as evidence that Misskelley knew details only someone present at the crime would know. Misskelley. . .

Stevie Branch had the left side of his face gouged around the jaw. In citing the passage in Misskelley's confession, Fogleman said: But

when you listen to it, what you're going to find is they ask him, it

says something about a boy and where was the person cut? He

[Misskelley] says, in the face. Now, in all this stuff that,

that

Mr. Stidham put on about this knowledge, this stuff in the paper about

they were all sexually mutilated and that kind of thing.

Nothing

in there about a boy being cut in the face. They were beat up

real bad, but nothing, nothing about someone being cut in the face.

[Fogleman closing argument]

There are several problems with this, the first being a victim having an injury to the jaw was in the newspaper. Byers,

father of Christopher Byers, said Gitchell told him one youth had been

hit above the eye, a second's jaw was injured, and the third "was worse

than that." [West

Memphis Evening Times, May 7, 1993]

Furthermore, the police showed Misskelley a picture of Michael Moore on the autopsy table. Most of his body was covered, with his face visible. Along with multiple superficial lacerations, Moore had a prominent cut on his face as noted by the medical examiner. On the left

forehead was a 1 5/8 inch by 1 1/8 inch abraded

laceration. [Michael Moore autopsy notes]

Having been shown the photo of Moore with facial bruises and a cut to the head, Misskelley responded by ascribing injuries to Moore. This was a pattern in the confession, the police give him one set of information, Misskelley repeats it back. From early in the confession: Det. Ridge:

Which one of those three boys is it you say Damien hit? (Misskelley

points to a picture) The third picture which will be. . .

Misskelley: Michael Moore. [Misskelley confession, June 3, 1993] Although Misskelley said Moore, he pointed to the picture of Byers - even though the name was on the photo. He was corrected by the police. "Okay, so you saw Damien strike Chris Byers in the head?" [Det. Ridge, ibid] (Misskelley hadn't said head.) The fact that Misskelley pointed at the Chris Byers photo would have continued significance because this would be the only photo he chose for his further identifications. The injury to the groin area. And

then they say, well, was, where was another boy cut? At the

bottom. He ends up, he says, in the area of the groin

area. Now, is, is all of that just coincidence that he says

that? Or,

is it as Mr. Ofshe says, that somehow these devious officers

manipulated the defendant into saying things that weren't

true? [Fogleman, closing argument]

[Misskelley] describes the castration of that particular boy. . . [Davis, closing argument] The defense presented that the information was available in the press. From The Commercial Appeal : An

Arkansas State Police broadcast alerting regional authorities to the

slayings said the hands of the boys had been tied behind their backs

and that they had been sexually mutilated. [Commercial Appeal, May 7,

1993]

It became a matter of contention that this report had wrongly said "they," i.e., all of them, had been sexually mutilated. In another article Gitchell offered a partial correction. Gitchell

would not comment on published reports that the boys' bodies were

mutilated, but he said that they were bound hand and foot.

"Not all of that report was accurate. I've refused to comment

on

what part was inaccurate, for investigative purposes," Gitchell said.

[West Memphis Evening Times,

May 7, 1993]

Furthermore, the statement cited above, "Gitchell told him one youth had been hit above the eye, a second's jaw was injured, and the third 'was worse that that.' [West Memphis Evening Times, May 7, 1993] also narrows down the number of victims with such a dramatic injury. Did Misskelley describe Byers groin injuries in the confession? Or as prosecutor Davis contended, the castration? In the affidavit for the warrants, the police were even more specific, declaring, "Misskelley stated that he witnessed the cutting of the penis of Chris Byers by Jason Baldwin." [Exhibit B, Search Warrant] In contrast, the confession says: Det. Ridge:

Alright, another boy was cut I understand, where was he cut at?

Misskelley: At the bottom Det. Ridge: On his bottom? Was he face down when he was cutting on him, or Misskelley: Mm-hmm. Det. Gitchell: Now you're talking about bottom, do you mean right here? Misskelley: Mm-hmm. Det. Gitchell: In his groin area? Misskelley: (overlapping) Mm-hmm. Det. Gitchell: Okay Det. Ridge: Do you know what his penis is? Misskelley: Mm-hmm, that's where he was cut at. [ibid] But what part of the above did Misskelley say? Det. Ridge:

Alright, another boy was cut I understand, where was he cut at?

Misskelley: At the bottom Misskelley: Mm-hmm. Misskelley: Mm-hmm. Misskelley: Mm-hmm. Misskelley: Mm-hmm, that's where he was cut at. [ibid, police comments removed] The rest was filled in by police, with Misskelley agreeing to the police version. Misskelley was then asked to identify which child had these injuries. Det. Gitchell:

Which boy was that?

Misskelley: That right there. (pointing) Det. Gitchell: You're talking about the Byers boy again? Misskelley: Mm-hmm. [ibid] As Gitchell noted Misskelley pointed to the photo of Byers again, the same photo he had identified as Michael Moore. Misskelley would point yet again to the photo of Byers when he identified which child was strangled to death. (None of the victims had signs of strangulation.) Misskelley:

That one right there.

Det. Gitchell: Now, you're pointing to the Byers boy again? Misskelley: Mm-hmm. Det. Ridge: How was he actually killed? Misskelley: He did, he choked him real bad like. [ibid] Given an opportunity, Misskelley became even more equivocal in what he saw - or didn't see. Det. Ridge:

Alright, is that where he was cutting?

Misskelley: That's where I seen them going down at, and he was on his back. I seen them going down right there real close to his penis and stuff and I saw some blood and that's when I took off. [ibid] Injuries to the ears. You've

also got another factor, that's the ears. The defendant tells

about the kids being grabbed by their ears. And you heard the

medical examiner's testimony, whatever the purpose for grabbing the

ears, this defendant in his statement says they were grabbed by their

ears. And if you'll look at that you'll see that's exactly

what

he says. [Fogleman

closing arguments]

In the confession, Gitchell began this line of questioning by telling Misskelley the children were forced to perform oral sex by being held - ruling out other means such as threats or intimidation. "How did, how did, they force these boys to have oral sex on them? How did they have a hold of them?" [Misskelley confession, June 3, 1993] It then took twelve exchanges before Misskelley said that they held the children by the ears. Misskelley first said they were held by the arms (once) and then by the head (four times). Gitchell asks four times if they were held "up here." What Gitchell was demonstrating when he said "up here" is not mentioned. Gitchell testified that Misskelley was demonstrating holding by the ears before he used the words. Gestures cannot appear in the audio recording, however in the transcribed confession says Misskelley indicated "by the ears" after the first three exchanges and one instance of Gitchell saying "up here." In spite of this, it required Gitchell another nine exchanges for "clarification." By the arms, by the head - it is clear that Gitchell would not stop until Misskelley had given him the answer he wanted, no matter how many guesses in what is obviously a limited number of methods to hold someone to perform this action. Annotated passage: Gitchell: How did, how did,

they force these boys to have oral sex on them? How did they have a

hold of them?

(Gitchell has made clear the method used was by force and involved holding) Misskelley: One of them had them, had them by the arms while the other one got behind them and stuff. (Misskelley, an amateur wrestler, offers up a wrestling hold) Gitchell: Did he ever hold him up here or (The phrase "up here" is meaningless without a gesture.) Misskelley: Uh, the one that was holding him up there at the front grabbing him by his headlock. (Misskelley offers a specific wrestling maneuver.) Gitchell: Had him in a headlock? Did he, did he have him any other way? (Gitchell continues to search for another answer.) Misskelley: He was holding him like this by his head like this and stuff. (Included on transcript: Note: was indicating the victims being held by their ears) (The transcript says Misskelley made a gesture consistent with the injuries on the ears.) Gitchell: Could he have been holding him up here like that? (In spite of the claimed gesture, Gitchell feels the need to offer another or the same suggestion.) Misskelley: He was, I was too far away he was holding him right there by his head like this (Included on transcript: Note: showed the same as above) (Misskelley is now trying to claim he was too far away along with repeating the answer.) Gitchell: So, so Misskelley: And he was pulling him. (snip; several exchanges until they return to the subject of holding the ears) Gitchell: And they would hold, you, tell me again about their hands on, I mean I know you're, you're holding it up here. (in spite of the fact that Misskelley has supposedly indicated what happened, Gitchell returns to the subject) Misskelley: It was up here by their heads and stuff and was just pulling and stuff. Gitchell: Alright, so they are up here, had their hands (Gitchell is still trying to clarify this.) Misskelley: By their ears and pulling them and stuff. Gitchell: Alright, okay, say, say that again for me now. Misskelley: Hold them by their head, by the ears and pulling. (The taped confession ends with this.) Three perpetrators, three weapons. Fogleman made the argument that the fact that the minimum number of weapons, three, matched the number of perpetrators was indicative that Misskelley had insider knowledge. You've

got three guys supposed to be involved in this, the defendant, Damien

and Jason. How many weapons did the medical examiner say that

he

could put a minimum number on? Three. At

least two

club type weapons. I mean, you don't have to be an expert to

look

at these photographs and know that those injuries were not caused by

similar type things. It's obvious that these were caused by

smaller object, these by a larger object. Then you got the

knife. Is it a coincidence again that we got three

weapons? [Fogleman

closing arguments]

Fogleman was referring to this exchange with the medical examiner, Dr. Peretti. Davis:

Okay, so would it be fair to say that, at least three different weapons

caused--one causing injury to the top of the head, one to the back and

one to the genital area?

Peretti: Yes. [Dr. Peretti testimony, Misskelley trial] This argument is somewhat confusing. Misskelley didn't describe two different sizes of sticks in his confession. He mentioned one "big old" stick and one folding knife. Furthermore, the prosecution entered two large sticks into evidence as potential weapons. Misskelley didn't describe three different weapons in total. While Peretti agreed at least three weapons causing the abovementioned specific injuries, he never suggested three weapons in total. Finally, Misskelley was adamant he did not cause any injuries, so why ascribe a third weapon for a third person? Trying to transform this Rorschach blot of a statement into guilty knowledge is indicative of a lack of meaningful information in the confession. Minimization by naming Michael Moore as the one he was involved with. He

also says that and this is in a sense corroboration of what he says in

his statement. Mr. Holmes says that it is natural for a

person to

try to lessen their involvement. Out of all three of these

kids,

for the defendant to associate with himself with. As far as

one

he dealt with. Which one did he pick? He picked

Michael

Moore, right? Which of the three boys didn't have any torture

type of mutilation to him? Michael Moore. Is that

coincidence? Or did the police somehow say, well, this would

be a

good scenario here. We'll, we'll get him to admit to it, but

we'll only have him involved with the one of them who wasn't hurt too

bad. No. It's not coincidence. It's not

an

accident. It's not a guess. [Fogleman closing

arguments]

Lessening one's involvement, also called minimization, is a common feature of confessions. It seems that Fogleman is arguing that somehow, because Misskelley associated himself with Moore, that Misskelley correctly picked the victim who would minimize his involvement. One problem is that this is a seeming misunderstanding of minimization. Minimization involves lying to make one seem less culpable. If Misskelley was lying when he claimed involvement with Michael Moore to minimize his crime, there is a fundamental flaw. Although Michael Moore did not have mutilation wounds, he had far more injuries identified on his autopsy report than did Stevie Branch, 63 to 21. And if he was lying to minimize his involvement, why say he did anything at all beyond observing? Misskelley identified what Jason was wearing. She

[Tabitha Hollingsworth] also said that they were wearing black and that

Domini had holes in her

knees. Do you remember that? You get your notes and

refer back, think

back about that. Now, what did the defendant say about what

Jason was

wearing? All black, one of these shirts with a skull on

it. And this

is in the tape about what he was wearing. And how did he

describe the

pants he was wearing? He said they had holes in the

knees. At night

along the service road, Domini has red hair. Jason Baldwin,

slight,

slightly built, long hair, pants with holes in the knees.

That's one

thing that corroborates the confession. [Fogleman

closing

arguments]

This is one of the claims, supposedly evidence, that makes this case so bizarre. In the Misskelley trial, Tabitha Hollingsworth testified she witnessed her cousin, Domini Teer, on the road near the crime scene. The prosecution contended that she actually saw Jason Baldwin. Furthermore, the prosecution said the clothes Tabitha Hollingsworth testified Domini was wearing were the same as what Jessie Misskelley said Baldwin was wearing. Only they weren't. They didn't match color or design. Fogleman: What

color clothes was Domini wearing?

Tabitha: She was wearing some black pants that kind of had flowers on them. Fogleman: Okay,

and what about a shirt?

Tabitha: Black. Fogleman: Was there anything about her pants? What was the condition of the pants? Tabitha: It had holes above the knees. [Tabitha Hollingsworth testimony, Misskelley trial] Tabitha Hollingsworth testified they were black pants with flowers on them. They had holes above the knees. The shirt was black. Misskelley said: Misskelley: He

was wearing some blue jeans and boots, like army boots like,

Det. Ridge: Army boots? And what kind of a shirt, you know everybody wears a special shirt for different things. Misskelley: He was wearing a, a Megadeth shirt. Det. Ridge: A Megadeth. Misskelley: Or maybe it was a Metallica. [Misskelley confession, June 3, 1993] Misskelley went on to say the jeans ". . .had holes in them and the knees and stuff" and the shirt had a scratched skull on it something like." [ibid] Tabitha testified: black pants with a flower pattern and holes above the knees. Misskelley said: blue jeans with no pattern mentioned and "holes in them and the knees and stuff." Tabitha testified: a black shirt, no design mentioned. Misskelley said: a Megadeth or Metallica design shirt with a scratched skull, no color mentioned. The only thing agreed on is holes in the pants, and even then not the location. If the taller Baldwin were wearing Domini's pants (as was contended), the holes above the knees would have been further above the knees. Two other Hollingsworths testified to the same clothing on Domini in the Echols/Baldwin trial. Said the clothes of the victims were removed before they were tied. Have they

got their clothes on when you saw them tied? [Fogleman

closing argument, quoting Det. Ridge in the Misskelley confession]

This was discussed above. It is an example of Misskelley giving information that is logically consistent with the facts. It is as Fogleman points out a leading question. This is the first instance in which the children being naked is brought up. Ridge's question assumes Misskelley saw them tied, in spite of another exchange that has Misskelley absent when they were tied. Det. Ridge:

Okay, when you came back a little bit later, and all three

boys are tied?

Misskelley: Mm-hmm. [Misskelley confession, June 3, 1993] A question of tennis shoes Fogleman argued that Misskelley correctly identified his tennis shoes and what happened to them. Do

you remember what the defendant said in his statement about what he did

with his tennis shoes. And what kind of tennis shoes they

were? He said he gave them to a guy named Buddy

Lucas. And

he described in his statement that they were white and blue

Adidas. Detective Ridge testified that he went to Buddy

Lucas',

and, lo and behold what did he get from Buddy Lucas? The

white

and blue Adidas. Is that a coincidence? I think

not. [Fogleman

closing arguments]

This is related to these statements in Misskelley's confession. Det. Gitchell:

What kind of shoes did you have on?

Misskelley: White and blue Adidas. [snip] Det. Gitchell: And who has those shoes now? Misskelley: Buddy Lucas. [snip] Det. Gitchell: Why, why does he have your shoes? Misskelley: We went, we was coming home one day and it was raining and he didn't have nothing else to wear so he put on one of my shoes. [Misskelley confession, June 3, 1993] These shoes did not have any trace evidence connecting them to the crime. All Misskelley did was correctly identify a pair of shoes as once being his. The Mistakes in Misskelley's Confession Fogleman also dealt with matters in which Misskelley was wrong. Which ones

is he wrong on? Two things, time and rope. [Fogleman closing

arguments]

A more reflective list of matters about which Misskelley was wrong is much longer.

Having said time was one of only two mistakes, Fogleman went into detail explaining Misskelley's problem with time. "He was telling what he knew, despite his faulty memory. And despite his gas huffing and alcohol abuse." [Fogleman closing arguments] Fogleman derided Dr. Ofshe for his own memory problems or "misrepresentations" regarding the issue of time. Both of these centered around phone calls and who during the confession brought up the time as being morning - or night. [With

heavy sarcasm] Ofshe tells you where the transcript shows Detective

Ridge said nine o'clock in the morning, that the transcript's

wrong. That was Jessie that said that, according to

Ofshe.

Listen to that tape. I don't believe you'll have any trouble

distinguishing between Detective Ridge's voice and the defendant's

voice and it is clearly Detective Ridge saying nine o'clock in the

morning. [ibid]

Detective Ridge does say nine o'clock in the morning - when referring to a phone call Misskelley received. Misskelley says nine o'clock in the morning - when referring to the time they went to the Blue Beacon woods, the alleged scene of the murders. The time of the phone call was of marginal relevance - whether Misskelley knew when the kids were murdered was very relevant. If the jury had followed Fogleman's instructions as he suggested and examined what Fogleman claimed, they would have lost confidence in him - again and again. It was

the defendant who first brought up night. Now why Ofshe tried

to

pass off to you-all that the police had introduced night, I don't

know. Was he wrong, just wrong, mistaken, not have a grasp of

the

facts? Or was he misrepresenting to you? [ibid]

Technically, Misskelley first used the word "night" - after the police asked him about that "evening." This question was also in reference to a phone call Misskelley said he received. Det.

Ridge:

That is, it was like early in the day, but you don't

know exactly what time. Okay, cause we got, I've got some real

confusion with the times you're telling me, but now, this 9 o'clock in

the evening call that you've got, explain that to me.

Misskelley: Well after, all of this stuff happened that night, that they done it Det. Ridge: Okay. Misskelley: I went home about noon, then they called me at 9 o'clock at night, they called me. [Misskelley confession, June 3, 1993] Misskelley says he is referring to the night of the day they "done it." He went home at noon after the crimes, and then at night the call came - at least in response to the leading question of the police. Fogleman goes on to say "In the second statement, they cleared up the time." When Misskelley's first confession was originally put to the judge, the judge rejected it as a basis for warrants, asking for a clarification, in particular of the time. The beginning of Misskelley's second statement begins with this clarification: Det.

Gitchell: Jessie,

uh, when when you got with

the with the boys and with Jason and Baldwin when you three were in the

woods and then the little boys come up, about what time was it? When

the boys came up to the woods?

Misskelley: I would say it was about it was about five or six, five or six. Det. Gitchell: Now, did you have your watch on at the time? Misskelley: Un-uh. Det. Gitchell: You didn't have your watch on? Misskelley: Un-uh. Det. Gitchell: Uh, alright you told me earlier around seven or eight or, wh-which time is it? Misskelley: It was seven or eight. Det. Gitchell: Are are you sh- Misskelley: I remember it was starting to get dark. [Misskelley confession, June 3, 1993] There is no recorded statement of Misskelley saying it was around seven or eight. Gitchell testified that the information had come from Misskelley (presumably off-tape). As Fogleman saw it: The

bottom line in this case is these officers' integrity, Inspector

Gitchell and Detective Ridge, there is absolutely not one iota of

evidence that they have told anything other than the truth in this

courtroom. [Fogleman

closing arguments]

Fogleman sums up Misskelley's confusion with time. "Finally, he says it was starting to get dark. He abandons referring to it by time because he has no concept of time." [ibid] Rope Fogleman then goes on to offer the following as a partial explanation as to why Misskelley didn't clear up the matter of the rope. In the second statement, they

cleared up the time. [snip] If

you will go back and listen to the tapes you will find there is nothing

said about what they are tied with until the second statement anyway.

It was in the second one, but it was not cleared up. [ibid]

Conclusion There are many matters in the confession in which Misskelley made statements that could have been wrong or right - there is just no evidence either way. For those that can be compared to the evidence, the number of items Misskelley got wrong far exceeded the correct items; he should have been able to guess his way to a more accurate statement. The prosecution's claim of inside knowledge included some items which required a generous interpretation of his confession and other items which had no relation to the confession. The contorted, unreal and bizarre connections the prosecutor made between the confessions and the facts, such as a misrepresented correspondence between Baldwin's and Teer's clothing, should have only served to demonstrate there was no good evidence. The prosecution's summary of only two incorrect matters in the confession was disingenuous and "misrepresentative." His ridiculing of expert witnesses was shameful and made a mockery of justice by associating it with the worst of small town prejudices. Having witnessed the proceedings, Bob Lancaster of the Arkansas Times wrote a commentary at the end of the trials. He said, "When the prosecution rested the state's case, about all it had proved was (1) that the murders had indeed occurred, and (2) how the victims died." Continued in The Case for Innocence, Jason Baldwin. |

![]()

|

Copyright © 2008 Martin

David Hill

|

|

Site Design By Michael

Gillen

|