Jivepuppi.com

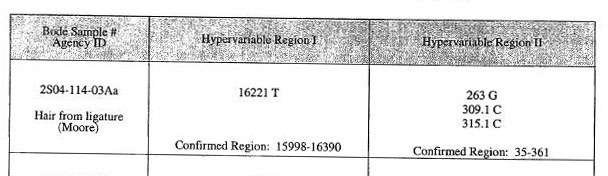

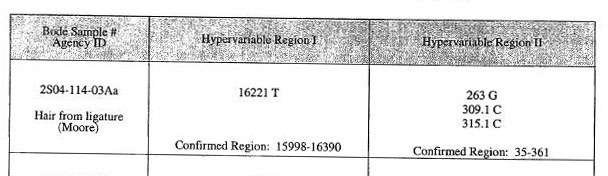

Sequence

data from a hair from Moore's ligature.

A Twilight Kill, Part Eleven: DNA

DNA encodes our traits; we are distinct

individuals

because of the makeup of our DNA. In turn, our DNA can be used to

identify us. Present in tissues and secretions often found at crime

scenes including blood, semen and hair, it can be the ideal forensic

tool, the ultimate arbiter of innocence or guilt.

In this case, critical biological samples were taken

from the victims, from suspects and from the collected evidence. The

state and the appeals attorneys agreed to examine: fingernail scrapings

from the victims; tissue samples from the ligatures; swabs from

each victim; cuttings from their clothes; loose hairs recovered from

the victims including hairs found in the ligatures;

hairs found

on the victims clothing, the morgue sheets and at the crime scene; and,

several miscellaneous items.

Biological specimens were also obtained during the

investigation from 44 other suspects and family members for matches or

exclusion. These samples could also be examined in future tests.

DNA Results

In the DNA Status Report filed with the

appeals,

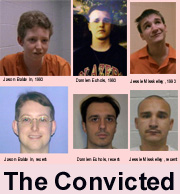

none of the DNA sequenced matched any of those in prison for the crime.

Almost all of the DNA from the crime scene matched the victims. Hairs

that previously had been found "microscopically similar" to those of

Damien Echols and Jason Baldwin did not come from them. The report went

on to say, "Although most of the genetic material recovered from the

scene was attributable to the victims of the offenses, some of it

cannot be attributed to either the victims or the defendants." [DNA

Status Report, July 17, 2007]

Partial results found nuclear DNA belonging to

neither the victims nor the convicted on the penile swabs from Stevie

Branch and Michael Moore suggestive of criminal contact. Hair shafts

only contain mitochondrial DNA. The convicted were excluded as the

source of any of the hairs. The following six hairs each had different

individual profiles, not matching the victims or those in prison:

- Hair from Michael

Moore ligature

- Hair from Chris

Byers ligature

- Negroid hair

fragment, morgue sheet

- Hair from scout

cap (only partial sequence available)

- Hair from tree

stump

- Dyed hair from

sheet used to cover Chris Byers

The hair from

Michael Moore ligature had a single nucleotide change from the

mitochondrial DNA of a sample gathered from the home of Terry Hobbs -

the stepfather of the victim, Stevie Branch. With a single nucleotide

difference, he can not be excluded as a possible source. Stevie

Branch's mother, Pamela Hobbs, says

she believes her ex-husband may have committed the crime and has come out in favor of a retrial.

Some material failed to amplify, including those

from the Kershaw knife and a hair from Michael Moore's pants.

The exclusion of the convicted as sources of the

material gathered from the crime scene is powerful evidence of their

innocence. Someone else left DNA on the penises of Michael Moore and

Stevie Branch indicative of a sexual crime. Notably, Chris Byers had

his genitals mutilated and could not be thus tested. The hairs from the

ligatures of Moore and Byers may well point to the killer.

The Power - and Impotency of DNA Fingerprinting

Through methods that can match even small

amounts of

genetic material to the person who deposited it, DNA has become a

torchlight illuminating the deficiencies of our judicial process.

Convictions based on eyewitness identification, hair "matching,"

jailhouse snitches, even confessions to police have been

found lacking.

In the first application of DNA fingerprinting, the

police had the confession of 17-year old Raymond Buckley for murder and

rape. Suspecting the same perpetrator was guilty in a second case, they

tested his DNA versus semen gathered from the two cases. The police

were half-right: the cases were the same perpetrator, but not Buckley.

Eventually they matched the DNA to the true killer.

Even when DNA excludes a convict the judicial

process often turns a blind eye. Clarence Elkins was convicted of the

rape and murder of his mother-in-law. After years in prison, the DNA

from the semen left in the victim was shown to be someone else's.

An evidentiary hearing was called. Elkins was denied a new trial.

Returning to prison, he encountered a fellow inmate who was a rapist

and a neighbor of the victim. He pocketed some discarded cigarette

butts from the man and sent them to his family so they could get a DNA

fingerprint from the saliva secretions. The DNA matched, as did a more

properly obtained sample.

A ridiculous standard was set for Elkins - he had to

find the killer himself while in prison. The judicial process is

negligent in admitting its mistakes. They would have to admit

complicity in half-baked verdicts that relied on prejudices and

strained evidence. Although there are seldom financial judgments in

favor of those proven wrongfully convicted, a fear of lawsuits can

drive self-interest over that of justice. Besides, for the authorities

involved, it is not their own lives they are throwing away.

Horrific crimes arouse fears and prejudices we

normally lock away in a deep vault of our minds. Unleashed, reason is

banished. In this case, there was not a piece of evidence that wasn't

compromised or stretched beyond reason. The tainted and contrived

evidence, the lies and last minute revelations, the compromised and

flawed witnesses were not coincidental. The state was trying to make a

case that just didn't fit the suspects. DNA, science and reason do not

point toward the convicted. DNA evidence is impotent in the face of

willful ignorance.

- Two bands, not

matching

Stevie Branch's DNA, were present on the sperm fraction from the penile

swab. D16S539, bands 8, 11.

- A single

additional band,

not matching Michael Moore's DNA, was present in the nonsperm fraction

from the penile swab on Michael Moore. D5S818, band

12.

A single suspect with these three

bands would make a likely candidate to be the killer.

Continued in A Twilight Kill, Part Twelve: Whodunnit.